We use cookies

Using our site means you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies. Read about our policy and how to disable them here

We've teamed up again with Malcolm Fare, our expert in fencing history. After the history of foil, epee and sabre fencing and the development of fencing kit, this time we're having a look into fencing masks in the past, present... and maybe the future?

by Malcom Fare

The head has always been vulnerable in combat and the British Museum has a remarkable mask from Roman times: a gladiator’s helmet with metal grill sections covering the eyes [Fig. 1].

Another extraordinary helmet, dating from AD600, was found at the Sutton Hoo ship-burial site. It includes a face mask with eye sockets, eyebrows and a nose which has two small holes cut in it to allow the wearer to breath freely [Fig. 2].

In medieval times jousting knights would wear massive helmets bolted on to their armour.

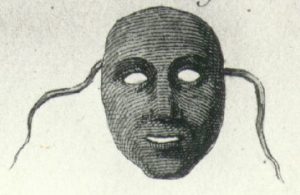

But when fencing became established as an elegant pastime for gentlemen needing to learn the art of self-defence, there was no simple and convenient means of protecting the face. If masks were used at all, they were made of leather or thin plate shaped to the outline of the face with small openings for the eyes and mouth, as illustrated in Domenico Angelo’s treatise, L’Ecole des Armes, 1763 [Fig. 3].

The French fencing master Texier de la Boëssière is generally credited with inventing the wire mask in the mid-18th century, although an encyclopedia of 1755 asserts that masks were not generally used except by beginners since good fencers had no need of them. Angelo forbade their use in his academy and his son Harry recalled1 that, while studying in Paris in 1773, he fenced with Lord Mazarene, “without a mask… when I swallowed some inches, button and all, of my noble opponent’s foil”. That year a caricature of the Duchess of Queensbury fencing with her servant was drawn by William Austin, in which she is shown wearing a face-shaped wire mask [Fig. 4].

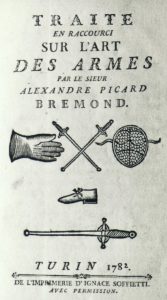

Yet by 1778 the Belgian master Nicolas Demeuse2 claimed that the advantage of wearing a mask was so great as to need no demonstrating, although he admitted that it was still unknown in many academies. He described a good mask as being light, but made of solid wire with a tightly meshed grill. It was tied on the head by two ribbons knotted behind. This type of mask is illustrated in the first book to show the device3 [Fig. 5].

A report in the Morning Post of a match between a French and an English fencing master in 1785 claimed that the Frenchman was used to fencing without a mask and the Englishman with one.

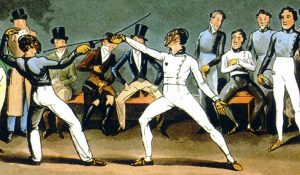

Thomas Rowlandson painted a scene in Angelo's Academy in 1787 depicting two tie-on masks [Fig. 6].

That same year James Gillray included a couple of similar masks in a corner of his print of the celebrated match between the Chevalier Saint-Georges and the Chevalière D'Eon before the Prince of Wales. But two years later a French print of this scene showed a mask of the more advanced spring-clasp design instead of using ribbons. Which type the Prince of Wales ordered in 1789 when he asked the fencing master Joseph Roland to supply six masks lined with blue silk remains a mystery, as they have vanished without trace. By the early 19th century, despite La Boëssiere the Younger4 declaring that the ribbon type was less liable to move during a bout and so safer, the spring clasp had become established as the most convenient method of attaching the mask to the head [Fig. 7].

Although the simple wire face cover with no ear or forehead protection was made from the late 18th century until the First World War, the introduction of a more mobile and athletic style of fencing in the 1830s gradually led to the development of a more complete form of protection. Ear covers were first added, then a section to protect the forehead, so that by the 1850s the whole mask had been strengthened and redesigned with a double spring clasp [Fig. 8].

Yet as late as 1862, the Under-Master of Westminster School, the Rev Thomas Weare, felt it necessary to emphasise the need to wear guards to the face and body while fencing; he had sustained a serious accident at Oxford while neglecting that simple safeguard.

Until the 1880s, the mesh was hexagonal in shape and hand-made, some finely crafted masks even being presented as prizes [Fig. 9].

Although a machine-made square mesh was introduced in England, many still preferred the traditional French model5. The need for a bib attached to the mask for added protection was mentioned as early as 18886, but it was not until competitions became commonplace in the early 20th century that bibs became a normal part of mask construction. In 1910 Souzy & de Lacam patented a stronger steel sheet mask pierced by 2 mm holes 3 mm apart.

Epeeists required a more substantial mask and a model with integral wire bib was developed in the third quarter of the 19th century [Fig. 10], superseded before the end of the century by the more flexible padded bib type.

Early sabre and sword exercise masks were of the semi-helmet type with a leather-clad superstructure over the head [Fig. 11].

The more robust fencing associated with singlestick and bayonet led to the development of a helmet design made either of stout wire with buffalo hide covering or of cane. The former was considered superior as the hand-woven cane helmet [Fig. 12] was apt to give way before a stout thrust and “let in the enemy's point to the detriment of eyes and complexion”.

Today, manufacturers use automated spot welding techniques [Fig. 13] to ensure that modern masks meet the highest safety standards.

(Editor's note: You can see a mask being produced in this video:

In 2000 transparent fencing masks came available but these were withdrawn from competitive use after contaminated and fake plastics had been used in some companies production. This meant some designs of the transparent mask could crack or fail and put the user at risk.

In 2019 new plastics that are stronger and conductive have been found and in the next 10 years plastic masks could finally replace the mesh mask designs of the 1900 century.

So, fencers, after this roundup, what do you say? Is the mask below the fencing mask of the future?

1 Angelo, Reminiscences of Henry Angelo, 1828

2 Demeuse, Nouveau traité de l'art des armes, 1778

3 Bremond, Traité en raccourci sur l'art des armes, 1782

4 La Boessière, Traité de l'Art des Armes, 1818

5 Cassell's Book of Sports & Pastimes, 1893

6 Desmedt, La Science de l'Escrime, 1888

Winner of the 2024 Kings Award for Enterprise